A Diplomatic Visit Turns Into a Heated Exchange

What was expected to be a friendly meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa turned into a tense confrontation. The discussion, held in the Oval Office on May 21, 2025, quickly escalated when Trump accused the South African government of failing to protect white farmers from what he called “genocide.”

Ramaphosa came to Washington hoping to reset relations with the U.S., which had cooled over disagreements on trade, race issues, and South Africa’s position on international matters such as Israel. But instead of focusing on trade, Trump turned the meeting toward what he described as violence and discrimination targeting white Afrikaner farmers.

“We have many people that feel they’re being persecuted, and they’re coming to the United States,” Trump said. “They’re white farmers, and they’re fleeing South Africa, and it’s a very sad thing to see. But I hope we can have an explanation of that, because I know you don’t want that.”

Trump’s Use of Visual Evidence and Ramaphosa’s Calm Rebuttal

At one point during the meeting, Trump dimmed the lights and played a video showing South African opposition politician Julius Malema chanting “Shoot the Boer, shoot the farmer.” The video then shifted to a field filled with white crosses. Trump told Ramaphosa and the reporters in the room, “Now, this is very bad. These are people that are officials and they’re saying kill the white farmer and take their land.”

He followed up by handing Ramaphosa a stack of printouts that he claimed showed white South Africans being killed. He said he was concerned that the South African government was not doing enough to protect them.

Ramaphosa, who was once a key figure in ending apartheid and building South Africa’s modern democracy, replied firmly but diplomatically. “What you saw in the speeches that were being made—that is not government policy,” he said. “We have a multiparty democracy in South Africa that allows people to express themselves. Our government policy is completely, completely against what he was saying.”

He also pointed to several white South Africans who were part of his delegation, including famous golfers Ernie Els and Retief Goosen, and billionaire businessman Johann Rupert. “If there was a genocide, these three gentlemen would not be here,” Ramaphosa said.

Trump fired back, saying, “But you do allow them to take land, and then when they take the land, they kill the white farmer, and when they kill the white farmer nothing happens to them.”

Ramaphosa responded simply, “No.”

The Controversial Land Reform Law

Much of Trump’s concern centers around South Africa’s new Expropriation Act, which Ramaphosa signed into law in January. The law allows the government to take land without compensation in certain cases, such as when land has been abandoned or is not being used productively. Supporters say it is a way to correct the severe land inequality created by apartheid, during which Black South Africans were stripped of property and forced into segregated areas.

Critics, however, see the law as dangerous. South African journalist Robert Duigan described it as “state-sanctioned racism.” He pointed out that the law allows the government to seize property based on broad justifications. “The Constitution already provides that discrimination is legal, so long as it is ‘fair,’ and fairness is defined precisely on the grounds of race in this country, and has been for some time, provided the race of the person being discriminated against is white.”

Zsa-Zsa Temmers Boggenpoel, a property law professor at Stellenbosch University, defended the law by saying it was meant to address the country’s colonial and apartheid past. “The country is still suffering the effects of this. So expropriation of property is a potential tool to reduce land inequality,” she wrote.

Despite the law being in place, experts agree that no land seizures have yet occurred. Anthony Kaziboni, a senior researcher at the University of Johannesburg, said, “There is no evidence of systematic land confiscation targeting white farmers or anyone else.”

Trump’s Refugee Order for Afrikaners

In February, Trump issued an executive order allowing white Afrikaner farmers to resettle in the United States as refugees. This marked a sharp reversal from his earlier suspension of the refugee program for people from other parts of the world.

Trump explained his decision by saying, “Because they’re being killed. And we don’t want to see people be killed. But it’s a genocide that’s taking place that you people don’t want to write about.”

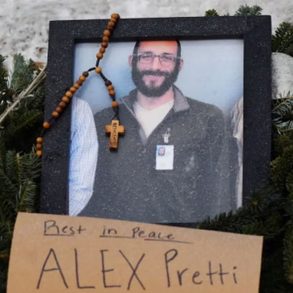

One refugee applicant named Mark, a South African farmer, told Reuters that he and his father were seriously injured during a violent farm attack in 2023. He said the staff at the U.S. embassy in Pretoria were “exceptionally friendly” and seemed to understand his fears. “I could feel they had empathy,” he said.

More than 30 applicants have already been approved, and over 67,000 people have reportedly expressed interest in the program.

However, critics both in South Africa and the United States argue that this program is selective and politically charged. South Africa’s foreign ministry issued a statement calling the policy “ironic,” saying it grants refugee status to a privileged group while denying protection to more vulnerable people from war-torn regions.

The Facts Behind the Violence

Experts say the claim of “white genocide” is misleading and not supported by crime data. Gareth Newham of the Institute for Security Studies said, “As an independent institute tracking violence and violent crime in South Africa, if there was any evidence of either a genocide or targeted violence taking place against any group based on their ethnicity, we would be amongst the first to raise the alarm.”

South Africa’s Police Service recorded 51 murders on farms during the 2022–2023 reporting year, compared to over 27,000 murders nationwide. Most of the murder victims in South Africa are young Black men living in poor urban areas.

Nechama Brodie, a journalist who has studied farm attacks, said, “South African media coverage of murder victims is extremely selective and creates a false depiction of who is most at risk.”

According to Newham, “The primary motive for almost all farm attacks is robbery, not race or politics.” He added that cases involving racial or political motives are “exceedingly rare and make up only a few percent of the cases recorded.”

Richard Breitman, a historian and genocide expert, explained that genocide requires clear intent to destroy a specific group. “It is not strictly a matter of numbers of victims, but of an organized effort, usually by a government or a political organization, to target a large percentage of a defined enemy group,” he said.

Kaziboni echoed this view, saying, “There is no indication of a state-sponsored campaign or intent to eliminate a specific racial group.”

The Broader Political Context

Trump’s comments come amid broader tensions with South Africa. The U.S. suspended aid to South Africa earlier this year and imposed 30 percent tariffs on South African imports, though those have been temporarily paused. Secretary of State Marco Rubio skipped a G-20 meeting in South Africa, calling the government “anti-American.”

Elon Musk, who was born in South Africa and has supported Trump’s concerns about Afrikaners, was also present during the meeting.

Ramaphosa tried to use the visit to strengthen trade ties, even bringing Trump a large coffee table book about South African golf courses and joking about sending a luxury plane like Qatar did. But the meeting will likely be remembered more for the confrontation than for the gifts.

Despite the heated moment, Ramaphosa remained composed and closed the meeting by invoking Nelson Mandela. “South Africa remains committed to racial reconciliation,” he said. “We are still a nation trying to heal from its past.”

Whether Trump’s claims will lead to policy changes or further divide U.S.-South Africa relations remains to be seen, but the clash revealed just how deep the disagreement runs over what is happening on South African farms.